Torrential rain, ravenous leeches, rainforest bramble, and the all-pervasive bean! Raine Zulueta, an undergraduate student at the University of California Berkeley, shares his field experience working with the field team in Ranomafana, Madagascar.

Time would pass in the car, and it felt as though I had gained a heightened sense of patience as I took notice of the passage of time. After around 15 hours, complete with dark winding roads up the mountainside, we would eventually arrive. Our legs numb and figuratively full of static, we turned in for two nights to relax before our very first day in the field. This was only the beginning of this two-month journey, and I was more than excited to take my first steps into the rainforest.

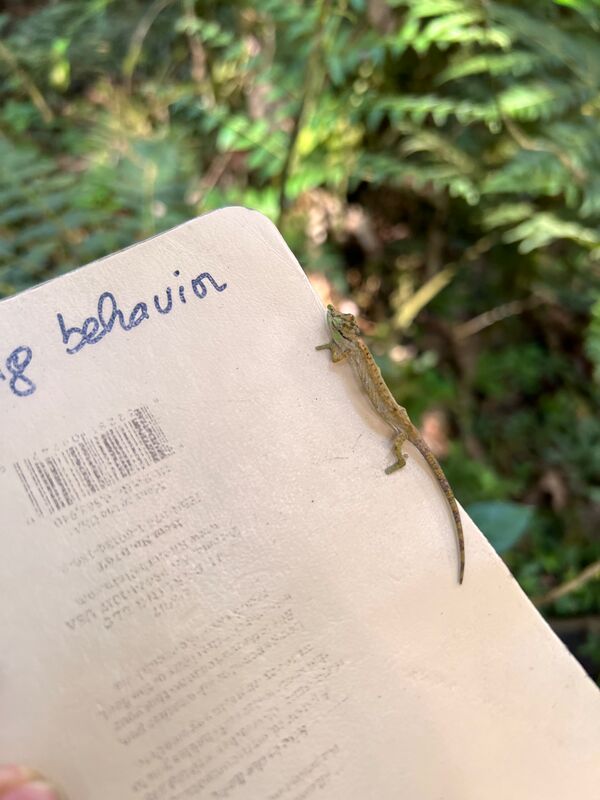

Time would pass, and by mid-July I had reached a rhythm and routine that felt like second nature. I would scurry down to the dining table, consisting of local wooden planks fastened with homely leather straps and cordage, beginning to devour my breakfast typically composed of either meat or eggs, rice, and beans At around 7:00 in the morning, we would begin to hike to the research site up the mountain, to begin our search for one of the three lemur species within the project: Eulemur rufifrons, Eulemur rubriventer, and Varecia variegata editorum. My responsibility within the project revolved around tracking and taking note of their behavior every five minutes. With my Rite-in-the-Rain handy, I would utilize different codes that would act as shorthand to describe what the lemurs were doing. For example, sleeping was shortened to “SL”, feeding to “F”, and even defecating and drinking water to “D” and “DW” respectively. To help gain experience in the different species, I would be placed onto one of the three different teams every week or so. This entailed mass amounts of learning through the experience itself, which I particularly enjoyed. It was fascinating to take note of the different temperaments and personalities that each species sustained, in addition to the behavioral patterns that would naturally arise. One of my fondest memories in the field happened during an Eulemur rubriventer follow. As you can likely assume, it rains quite a lot in the rainforest, and truthfully I expected the same if not more before arriving to Ranomafana National Park. But on this particular day, I had seen rain in a way I had never seen it before. It was truly torrential, hefty droplets of water plummeting at speeds and in sheer volumes unbeknownst to me as a Californian. We were bounding up the mountain, slashing through the rainforest foliage while chasing a red-bellied lemur as it sprung from canopy to canopy. Seemingly increasing in speed, the male lemur swiftly scaled the mountainside, the slashing of brush audibly constant, almost rhythmic. Crossing through ephemeral rivers, waterfalls, slippery rocks and more, we eventually reached the mountain’s peak. Upon our arrival we were greeted by a sight I hold dearly to my heart, what I think made this lemur follow so special: a lone E. rubriventer female sitting in the middle of a clearing, looking up at the canopy and rainfall misting her visage, almost in admiration. While the rain completely soaked all of our belongings, my backpack and rain coat dripping to the touch, I found solace in the cooling relief that it delivered as I found my body fatigued from the scramble up the mountain. This is but one of many memories created, stories encountered, and experiences lived, throughout this field season.

My association with field work, yet alone tropical fieldwork, could be expressed as a blank slate. Lemur research in the tropical rainforests of Madagascar is not where I saw myself five years ago, but I am genuinely more than grateful to have ended up where I did. As niche as this entire summer was, I firmly believe that this trip helped me find myself on levels deeper than I could ever imagine, all while learning what it means to conduct research and contribute to crucial conservation efforts.

Reconnection through pandemics and cyclones Jade Tonos is back in the field and shares her experience ... In many ways, 2022 has so far been a year of reconnection. As pandemic restrictions lift across the world and people return to their previous habits, many of us have specifically sought the joy of reunion. For many field biologists, the most important reunions have been their return to the forests, grasslands, coasts, wetlands, and mountains where they work. Like many others, I had to cancel my 2020 field season in Madagascar when the pandemic hit. This disruption threw my PhD completion plans out of sync and left me with the challenge of creating new projects and defending on time. After pulling that off, I was thrilled to join the Razafindratsima lab as a post-doc at UC Berkeley. This position brought immediate reunions, getting to see and work alongside the people I had missed from my work in Madagascar. It also brought the promise of a bigger reunion in the future, a return to Malagasy forests. I have now been in Madagascar for three weeks, filled with brilliant reunions and new encounters. Though when I began this journey, I did not expect to also encounter another reunion in-process: the return of Malagasy lemurs to forests damaged by recent cyclones. First Connections: People, Cities and Landscape

This year the visit was full of re-wirings, as I practiced my Malagasy and continued to fill out my mental map of the city after a long absence. It is always a pleasure to turn an unfamiliar corner to find yourself in a familiar place or to successfully navigate to a location you have only visited once or twice before. During this process, I rely heavily on colleagues and friends, and this year I was particularly happy to be greeted with familiar faces. After a week, I finally set out to Ranomafana. As always, it was a relief to leave the busy city for quieter landscapes, and though one may be inclined to despair at the lack of forests, it is hard to deny the beauty of the Malagasy countryside. Forest Connection  Black and white ruffed lemur in Ranomafana. Photo by Onja R. Black and white ruffed lemur in Ranomafana. Photo by Onja R. Arriving in Ranomafana is always a satisfying homecoming. Despite difficulties caused by the pandemic, I was glad to see the staff had barely changed. The forest, from the road, looked similarly unchanged. An expanse of green clinging to vast hills. The story drastically changed when I entered the forest; in the lowlands, the damage appears minimal; but as you climb further in and up you begin to encounter damage. The damage caused by the two cyclones in early 2022 is first apparent by single fallen trees blocking the path, eventually becoming whole sections of forest knocked flat across the trail, blocking it completely and forcing us to take alternative routes. These encounters leave me with a mix of sadness and admiration. The death of these trees is sad, but getting to witness their vast but shallow roots now exposed has left me with a better appreciation of the structure of this forest. These open locations also offer dazzling views of the whole forest stretching away in a way that may trick you into thinking they are never-ending. Though I did not notice during that first harrowing hike, it did become apparent soon afterward that the cyclone had also left the forest a quieter place. We did not hear groups of Black-and-white ruffed lemurs greeting the morning with their haunting calls. We did not encounter red-fronted lemurs dashing noisily through the forest in large groups. And no matter how hard I peered at lumps of reddish moss in the canopy, none of them unfolded to reveal themselves as a quiet and observant, red-bellied lemur family. Conversing with my local technicians and other researchers, the picture came clearly together. The cyclone severely affected the forest, damaging many of the largest fruit-producing trees, and hampering the ability of the rest to provide on their regular schedule. At the same time, reports of lemur groups venturing farther out of the forest than they ever have, keep coming. For a startling example, the black-and-white ruffed lemur, the shiest of the three primarily frugivorous lemurs, has been spotted snacking on bananas in the middle of nearby villages. Our project for the summer was focused on examining how the qualities and spatial distribution of fruits affect lemur behavior, movement, and seed dispersal. And though this situation throws a wrench in our plan, it also provides us with an opportunity to study the recovery of plant-animal interactions. These connections, severed by the cyclones, must recover as plants regain the resources to flower and fruit again and the lemurs return to the forest. I am eager to continue my work here and to be a front-seat witness to this reconnection between the displaced lemurs and the trees that feed them and rely on them for seed dispersal. Text and pictures by Jade Tonos

Mpikaroka mankafy manao sakafo anaty alaRindra Nantenaina, a PhD student at the University of Antananarivo, affiliated with the lab, shares a story about how she loves cooking in the field ... Tiako ny misakafo fa mbola tiako kokoa ny miaina ny natiora any an’ala Rindra no anarako, mpianatra mpikaroka, misehatra manokana amin'ny fifandraisan’ny zava-maniry sy ny biby mpamafy voa/vihy an’ala aho. Anisan'nyy fialam-boly tiako ny mandeha misakafo miaraka amin’ny namana rehefa mitoetra ao an-drenivohitra. Fa mbola tiako lavitra mihoatra an’izay anefa ny misitraka ny fitsokan’ny rivotra madio, ny mahita ireo zava-maitso isan-karazany ary ny maheno ny hiram-borona sy varika sy ny fikorianan’ny rano ao anaty ala. Nitsiry tany anatiko ny hevitra hanambatra ireo fialam-boliko roa ireo...

Teo no nitsiry tany anatiko ny hevitra hoe maninona tokoa moa raha ampisiana aty anaty ala aty izany karazan-tsakafo izany e!!! Sady mampiala voly rehefa tsy miasa iny, no manome fahafaham-po ny lela, ary mahavoky ny kibo. Angaha izay ihany, fa sady mizara fifaliana ho an’ireo mpiara-miasa any an-toerana ihany koa, satria vitsy amin’izy ireo no manana fahafahana hiakatra an-drenivohitra sy ho afaka ny hanandrana ny tsiron’ireo karazan-tsakafo ireo. Dia nanomboka nianatra nanao sakafo aho ... Ny olana anefa, raha izaho manokana tsy manana traikefa akory amin’ny fanaovana sakafo. Soa ihany fa amin’izao vanim-potoana izao, dia efa mivoatra be ny teknolojia, ka tsy ny asa fikarohana ara-tsiansa na ny toy izany ihany akory no afaka atao any anaty internet fa na ny fanaovan-tsakafo sy ny fikarakarana ao an-dakozia ihany koa, dia tena feno isan-karazany any. Arak’izany dia naka "recette" tamin'ny internet aho, toy ny fanamboarana mofo dipaina, mofo gasy, pizza, sandwich, crepe, cake, hamburger, beignet isan-karazany sns… Isaky ny miakatra miantsena any an-tanan-dehibe dia niezaka nanangona ireo singa rehetra ilaina amin’ny fanamboarana azy ireny aho. Matetika rehefa faran'ny herinandro, na amin’ny fotoana hafa tsy iasany, na rehefa haivariva avy miasa iny no manao sakafo izahay. Dia miezaka mamoaka "menu" iray isaky ny manao. Sady mianatra aho, arak’izany, no mampianatra ireo ekipa miaraka amiko ihany koa. Lasa fifaliana iombonanay ny fiarahana eo am-pikarakarana, maika moa fa rehefa injay vonona ny nahandro ka hiara-komana, dia tena samy finaritra avokoa ny rehetra e! Tsy hoe akory variana nanao sakafo izahay dia tsy vita ny fikarohana, fa tena nanampy anay hahatratra ny tanjona aza ny fiarahana. Ny kibo voky moa ny asa vita ara-dalana. Mampisy firaisam-po sy "ambiance" ary fahazotoana ao anaty asa ny fisian’ny fialam-boly tahaka an’izany. Lasa fialam-bolin’izy ireo koa ny fialam-boliko ...  Tombony azoko tamin’izany ny fahaizako nampiaraka ireo fialam-boliko anakiroa ireo: misakafo miaraka amin’ny namana sy ny miaina tontolo maitso any anaty ala, no mbola niampy fahaiza- manao ody ambava-fo isan-karazany hanohananay aina nandritra ny terrain. Ho an’ny ekipako kosa indray dia sady nahafantatra no nanandrana zava-baovao (karazan-tsakafo sy ny fanamboarana azy) izy ireo, no voky sy niala voly niaraka tamiko nandritra ny fotoana izay nanaovako niasako tany. Tsy nijanona ho anay teo amin’ny campement samy irery akory izany traikefa sy fifaliana izany, fa nentin’ireo ekipa nody tany an-tranony avy koa, sady dia nazoto nanao fampiharana mihitsy ary ry zareo rehefa tonga any anivon’ny ankohonany. Hafatra manokana ho antsika mpikaroka

Lahatsoratra nosoratan'i Rindra Nantenaina. Sary nozarain'i Rindra ihany koa.

Fieldwork in Madagascar in time of COVID-19Vero Ramananjato shares her recent experience conducting fieldwork in Madagascar this year.

When it became possible to travel ... Everything appeared to be a rush suddenly, and I was completely losing grip after eight months of a somehow calm schedule. The crowd I was facing when I first went outside of my neighborhood terrorized me. It was because not only I had to maintain a safe distance from them, but mainly because I had to readjust my ears and my eyes to hear so much noise and see so many people. I have also become so easily worn out. Whenever I come back from permit preparation, shopping for fieldwork, or just a short meeting out of my house, I am so tired that I can’t focus on any other works for the day. And I soon realize that the daily physical exercises I did at home are nothing compared to the daily morning walk I used to do before and the long and exhausting hikes in the forest. Fieldwork has become a real challenge… I have never been very fit, but 8-month being confined at home have completely knocked me over. Walking 20km a day used to be a breeze, but it has become torture, even on a flat trail! Sometimes, I even have asthma attacks after a 20-min mountain hike or foggy walk, although I didn’t have any for more than five years. The entire field team also had a hard time when we got back to the field. In the forest, we have become easily breathless and always needed some time to recover before starting our daily tasks. We had to leave our campsite way earlier than before to hike slowly. I should have thought about getting in good shape before going back to the field! Thankfully, the team was very encouraging and supportive. They are cheering me like an athlete who just finished a run when I finally reach them, while they have already been taking a long break from the hike. Ordering materials for the field has also become a challenge. Before, I would go directly to the different stores to see and buy what we need. But now, since most of the shops in Madagascar changed the way they operate, I have to call the store, ask for all the details I need to know about particular items, and then order the items. It is so much stressing because sometimes they don’t know what I’m talking about. Sometimes, they would just hang up when I ask a lot of details. Finding the right field equipment is also even more challenging than before now. Usually, when I don’t find a research item in Madagascar, I can ask a friend/colleague abroad to buy it and bring it to Madagascar when they come for fieldwork. This has never been an issue before. But now, since there are barely any flights coming to Madagascar, which are often limited to selected groups of people, I can’t find anyone who would get me the materials I need for fieldwork. I had to borrow some from our colleagues and collaborating organizations, which was not always practical because everyone was going to the field simultaneously after such a long pause. This made me realize, though, how much the field research in Madagascar relies on external help, but at the same time made me think about finding ways to build what I need with what we have on the island. After fieldwork, when I get back to the city, everything just seems overwhelming. Facing the rush, the crowd and the busy schedule have become a little bit irritating and frustrating. In the field, I only think about nature, my tasks, and the team, that I always feel relaxed despite any stressful situations that may happen. Also, I can always find time for myself and my plans, I feel the warmth of being supported by others again, and I put things in perspective in the long term. But, once I’m back home in the city, everything is just so overwhelming, especially because I need to distance myself to protect my loved ones; and seeing some irresponsible people makes it even worse. It’s hard to get back to that serene state in the forest. And I so wish I was back in my tent again! Safety first?!?Despite the efforts of the field team to follow all the safety guidelines in place during fieldwork, we faced challenges when it comes to our own safety and the safety of the local communities. To work in some of our field sites, we have to camp in some villages and/or interact with villagers. However, because they are not well-aware of the pandemic situation, no one is wearing masks in the villages, and some of them even see us as threats when we wear masks. Widespread conspiracy and rumors have reached the remote villages, unfortunately. Most of them believe that Covid-19 is a pure invention despite several cases in Madagascar and even in their villages. They also think that even if it exists, it won’t reach them as they are remote and far away from the city where the disease is attacking. Thankfully, they are open to discussion and learn. As a scientist and educator, I felt compelled to educate my fellow Malagasy about what I know. And my team members did the same as well. They would ask us a lot of questions. What is Covid-19, how it spreads, how can you protect yourself and others, what to do if they suspect a case, what progress science has made to treat and limit the pandemic, etc. We’ve also discussed how aggressing or killing wild animals out of the fear of being infected is definitely not the way to go. It has become one of our duties to do so every time we arrive at a new village. I believe it is the role of all field researchers, even if they are not experts in the matter, to educate the local communities about this pandemic and any other diseases and show them the best practices. Such remote locations don’t always have access to up-to-date information and often are vulnerable to conspiracy and fear-mongering rumors.

Text by Vero Ramananjato. Pictures courtesy of Hasina Rakotoarisoa, Vero Ramananjato & Finaritra Randimbiarison

Our collaborator Seheno Andriantsaralaza recently went on a preliminary fieldwork for the project investigating the dispersal mechanism of Madagascar's iconic, orphaned, baobab trees in the southwestern part of Madagascar, and shares some highlights of the fieldwork in these videos. Enjoy!

|

We're using this space to share updates on our adventures in the field. Archives

November 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed