|

Text by Jessica Stubbs

Thus, when the lab offered me the opportunity to become a Field Technician in Madagascar, I felt as if I was finally able to realize my ecological decree and ameliorate the dissonance between my most profound academic passion and personal experience. Armed with robust rubber boots, a plethora of ambiguous antibiotics, and an inexplicable sense of loyalty to the ecosystems and lemurs I was yet to meet, I was ready for anything. The first week in Antananarivo was a vibrant and kinetic rush of unfamiliarity and culture. Scouring the teeming markets for field supplies, absorbing my first words of Malagasy, and ambling along the restless streets was exhilarating. Most exuberant, was having the momentous privilege to experience lab member Vero’s wedding. Dancing in effervescent swirls of Malagasy family members, consuming heaps of aromatic ravitoto, and reveling in the cultural exuberance of the wedding traditions was a singular experience of exceptional joy. The entangled vibrance of Antananarivo was a sensorial introduction to Madagascar and only a nascent glance into the incredible country I was soon to explore. While driving to Ranomafana, the boisterous contours of the city melted into expansive verdant hills, imbricating agricultural fields, and meandering brown streams. The landscape was punctuated by lines of laboring zebus, rich piles of fresh bricks, intimate huddles of market sellers, opinionated discourses among geese, and clusters of enthralled children.

After a few days gathering our supplies and coordinating our research objectives, we set off through banana fields and up arboraceous mountains to our campsite to begin the real work embedded within the forest.

Meals consisted of rice and beans, showers were taken in the river's embrace, purpose was found in the lemurs, and community thrived among the people and biota around us. The endless onslaught of news cycles, inundation of messages and emails, and perennial duty of academic and professional tasks faded into the immediacy and immensity of the forest. The profound reduction in external stimulus honed my abilities as a conservation practitioner and allowed my somatic and cerebral capabilities to unify in the research, questions, and wildlife that enveloped me.

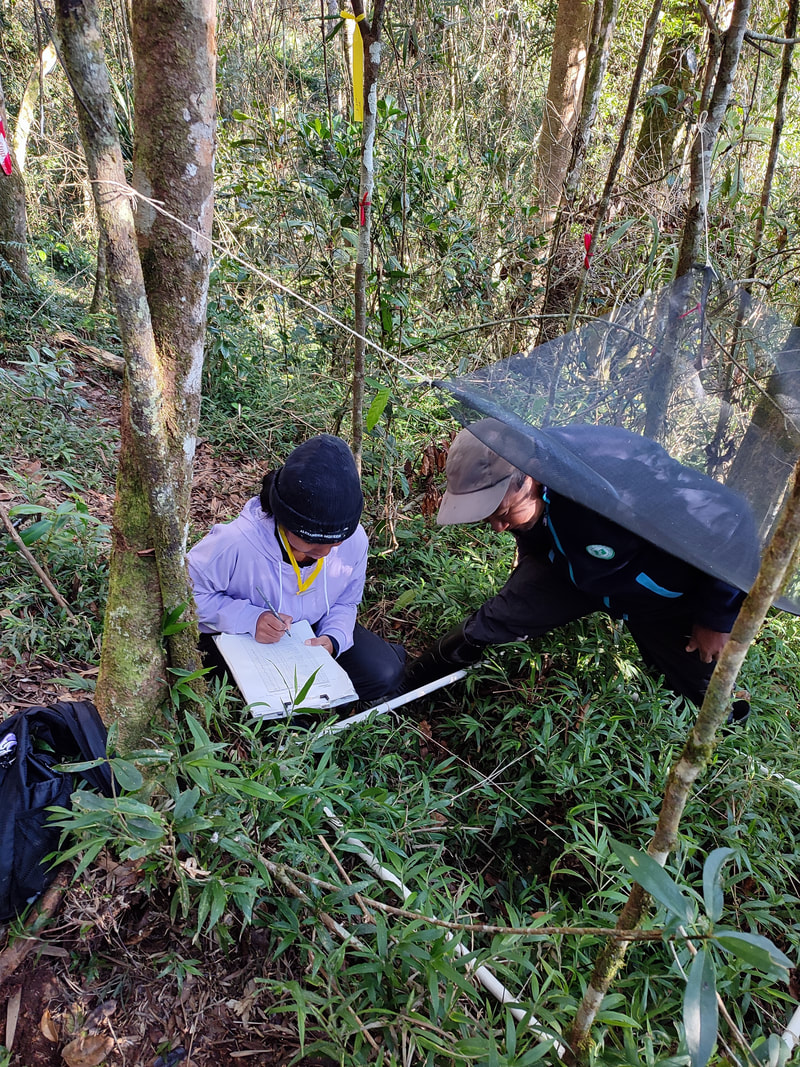

Everyday was met with a multitude of novel lessons, inspiring curiosities, interminable giggles, scientific inquiries, lemur connections, persistent leeches, and legions of rice and beans. Never before had I possessed so few material effects and external comforts, and yet felt so fulfilled. My mind was kinetic with research ideas, empirical conquests, and experimental propositions. After lemur follows, we would march to the lab (a makeshift arrangement of tarp and sticks) and dive into preparing fecal samples with multiple treatments to delineate how the lemur microbiome affects seed germination rates. Conducting innovative science in the middle of the forest truly instilled the importance of embracing constant agility, improvement, and adaptation in an environmental arena of finite resources and unlimited stochasticity. As an emerging conservation practitioner, these experiences fortified my scientific problem-solving dexterity and imprinted an enduring zeal for advancing research on the front lines of conservation. Beyond catalyzing the counters of my intellectual prowess, the endogenous connections and palpable kingship that developed with the lemurs and fellow field technicians were transformative. Camp members and field technicians became an instant troop of unwavering loyalty. Hundreds of hours spent in the forest welded us together interminably. Picking leeches off each other, sharing meals under the canopy, teaching plant varieties, exchanging languages, and collectively immersing in the centripetal intrigue of the lemurs infused every lemur follow with an immensity of supportive reciprocity. Back at camp, the enveloping sense of community transcended challenging conditions and crystallized into interrelational wisdoms, connections, and understandings. Playing dominos with fierce determination, boldly pioneering novel food concoctions, piling around the fire, and passing jugs of steaming burnt rice water around the table were liminal moments of enduring warmth. Punctuating our time at camp were both restful and exuberant sojourns at the ValBIo Research Station. There, we extracted DNA by processing our fecal samples utilizing advanced laboratory techniques. In the lab, I sharped my pipetting precision, gained confidence mixing fragile chemicals, and advanced my ability to curate immaculate lab playlists to foster the ideal musical feng shui for science. Spending afternoons in the lab, meals with impassioned researchers, and evenings organizing supplies and trading lemur stories with volunteers further reinforced my avidity and esteem for the imperative research we were conducting. From skillfully collecting lemur fecal deposits from the forest floor to methodically purifying and extracting genetic information from samples in the lab, I was developing a comprehensive understanding of advancing conservation research.

My Forest Adventure: Ten Weeks of Discovery and Learning Text by Diary Randriamora, a Malagasy student who spent last summer working with our research group in Ranomafana through the National Geographic Society's STEM Field Assistant Mentorship program

Working in a rainforest that rains a lot is itself also very challenging. One day, we had a heavy rainstorm on our way to our campsite in Valohoaka. The rain was so strong that it soaked my rain boots and made my feet swell. I also had many leeches stuck to my feet, which was very unpleasant. But I did not let that ruin my mood, because I knew that rain was essential for this tropical forest ecosystem. I embraced the adventure and enjoyed every moment!

I have a message for those who love research like me: don’t be afraid to try something you like and see as beneficial for you because there is always a good way behind adventure. Be determined to achieve your goals and don’t let them be just dreams!

Madagascar field updates summer 2023Text by Onja H. Razafindratsima This year, we decided to deploy a couple of GPS collars on the three large-bodied frugivorous lemur species in Ranomafana National Park to get a better sense of their movement patterns and activities. We worked with a team of experts in capturing and handling lemurs led by DVM Haja Rakotondrainibe. These GPS collars will allow us to investigate how lemur movement and foraging patterns change across seasons with varying fruit availability. I have been studying lemur ecology for more than a decade and this was the first that I got up close to my study species in their natural environment. It was exhilarating!

After spending quite some time in Ranomafana, I then joined my mentees in Ihofa, in the eastern part of Madagascar to check on their projects. I enjoyed very much the visit! Some pictures from the field can be found in this link.

Torrential rain, ravenous leeches, rainforest bramble, and the all-pervasive bean! Raine Zulueta, an undergraduate student at the University of California Berkeley, shares his field experience working with the field team in Ranomafana, Madagascar.

Time would pass in the car, and it felt as though I had gained a heightened sense of patience as I took notice of the passage of time. After around 15 hours, complete with dark winding roads up the mountainside, we would eventually arrive. Our legs numb and figuratively full of static, we turned in for two nights to relax before our very first day in the field. This was only the beginning of this two-month journey, and I was more than excited to take my first steps into the rainforest.

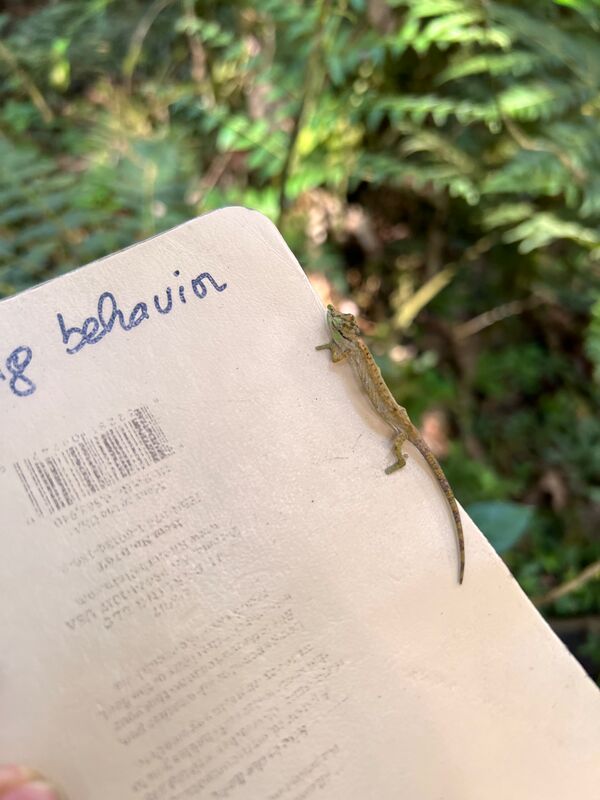

Time would pass, and by mid-July I had reached a rhythm and routine that felt like second nature. I would scurry down to the dining table, consisting of local wooden planks fastened with homely leather straps and cordage, beginning to devour my breakfast typically composed of either meat or eggs, rice, and beans At around 7:00 in the morning, we would begin to hike to the research site up the mountain, to begin our search for one of the three lemur species within the project: Eulemur rufifrons, Eulemur rubriventer, and Varecia variegata editorum. My responsibility within the project revolved around tracking and taking note of their behavior every five minutes. With my Rite-in-the-Rain handy, I would utilize different codes that would act as shorthand to describe what the lemurs were doing. For example, sleeping was shortened to “SL”, feeding to “F”, and even defecating and drinking water to “D” and “DW” respectively. To help gain experience in the different species, I would be placed onto one of the three different teams every week or so. This entailed mass amounts of learning through the experience itself, which I particularly enjoyed. It was fascinating to take note of the different temperaments and personalities that each species sustained, in addition to the behavioral patterns that would naturally arise. One of my fondest memories in the field happened during an Eulemur rubriventer follow. As you can likely assume, it rains quite a lot in the rainforest, and truthfully I expected the same if not more before arriving to Ranomafana National Park. But on this particular day, I had seen rain in a way I had never seen it before. It was truly torrential, hefty droplets of water plummeting at speeds and in sheer volumes unbeknownst to me as a Californian. We were bounding up the mountain, slashing through the rainforest foliage while chasing a red-bellied lemur as it sprung from canopy to canopy. Seemingly increasing in speed, the male lemur swiftly scaled the mountainside, the slashing of brush audibly constant, almost rhythmic. Crossing through ephemeral rivers, waterfalls, slippery rocks and more, we eventually reached the mountain’s peak. Upon our arrival we were greeted by a sight I hold dearly to my heart, what I think made this lemur follow so special: a lone E. rubriventer female sitting in the middle of a clearing, looking up at the canopy and rainfall misting her visage, almost in admiration. While the rain completely soaked all of our belongings, my backpack and rain coat dripping to the touch, I found solace in the cooling relief that it delivered as I found my body fatigued from the scramble up the mountain. This is but one of many memories created, stories encountered, and experiences lived, throughout this field season.

My association with field work, yet alone tropical fieldwork, could be expressed as a blank slate. Lemur research in the tropical rainforests of Madagascar is not where I saw myself five years ago, but I am genuinely more than grateful to have ended up where I did. As niche as this entire summer was, I firmly believe that this trip helped me find myself on levels deeper than I could ever imagine, all while learning what it means to conduct research and contribute to crucial conservation efforts.

Reconnection through pandemics and cyclones Jade Tonos is back in the field and shares her experience ... In many ways, 2022 has so far been a year of reconnection. As pandemic restrictions lift across the world and people return to their previous habits, many of us have specifically sought the joy of reunion. For many field biologists, the most important reunions have been their return to the forests, grasslands, coasts, wetlands, and mountains where they work. Like many others, I had to cancel my 2020 field season in Madagascar when the pandemic hit. This disruption threw my PhD completion plans out of sync and left me with the challenge of creating new projects and defending on time. After pulling that off, I was thrilled to join the Razafindratsima lab as a post-doc at UC Berkeley. This position brought immediate reunions, getting to see and work alongside the people I had missed from my work in Madagascar. It also brought the promise of a bigger reunion in the future, a return to Malagasy forests. I have now been in Madagascar for three weeks, filled with brilliant reunions and new encounters. Though when I began this journey, I did not expect to also encounter another reunion in-process: the return of Malagasy lemurs to forests damaged by recent cyclones. First Connections: People, Cities and Landscape

This year the visit was full of re-wirings, as I practiced my Malagasy and continued to fill out my mental map of the city after a long absence. It is always a pleasure to turn an unfamiliar corner to find yourself in a familiar place or to successfully navigate to a location you have only visited once or twice before. During this process, I rely heavily on colleagues and friends, and this year I was particularly happy to be greeted with familiar faces. After a week, I finally set out to Ranomafana. As always, it was a relief to leave the busy city for quieter landscapes, and though one may be inclined to despair at the lack of forests, it is hard to deny the beauty of the Malagasy countryside. Forest Connection  Black and white ruffed lemur in Ranomafana. Photo by Onja R. Black and white ruffed lemur in Ranomafana. Photo by Onja R. Arriving in Ranomafana is always a satisfying homecoming. Despite difficulties caused by the pandemic, I was glad to see the staff had barely changed. The forest, from the road, looked similarly unchanged. An expanse of green clinging to vast hills. The story drastically changed when I entered the forest; in the lowlands, the damage appears minimal; but as you climb further in and up you begin to encounter damage. The damage caused by the two cyclones in early 2022 is first apparent by single fallen trees blocking the path, eventually becoming whole sections of forest knocked flat across the trail, blocking it completely and forcing us to take alternative routes. These encounters leave me with a mix of sadness and admiration. The death of these trees is sad, but getting to witness their vast but shallow roots now exposed has left me with a better appreciation of the structure of this forest. These open locations also offer dazzling views of the whole forest stretching away in a way that may trick you into thinking they are never-ending. Though I did not notice during that first harrowing hike, it did become apparent soon afterward that the cyclone had also left the forest a quieter place. We did not hear groups of Black-and-white ruffed lemurs greeting the morning with their haunting calls. We did not encounter red-fronted lemurs dashing noisily through the forest in large groups. And no matter how hard I peered at lumps of reddish moss in the canopy, none of them unfolded to reveal themselves as a quiet and observant, red-bellied lemur family. Conversing with my local technicians and other researchers, the picture came clearly together. The cyclone severely affected the forest, damaging many of the largest fruit-producing trees, and hampering the ability of the rest to provide on their regular schedule. At the same time, reports of lemur groups venturing farther out of the forest than they ever have, keep coming. For a startling example, the black-and-white ruffed lemur, the shiest of the three primarily frugivorous lemurs, has been spotted snacking on bananas in the middle of nearby villages. Our project for the summer was focused on examining how the qualities and spatial distribution of fruits affect lemur behavior, movement, and seed dispersal. And though this situation throws a wrench in our plan, it also provides us with an opportunity to study the recovery of plant-animal interactions. These connections, severed by the cyclones, must recover as plants regain the resources to flower and fruit again and the lemurs return to the forest. I am eager to continue my work here and to be a front-seat witness to this reconnection between the displaced lemurs and the trees that feed them and rely on them for seed dispersal. Text and pictures by Jade Tonos

|

We're using this space to share updates on our adventures in the field. Archives

May 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed