|

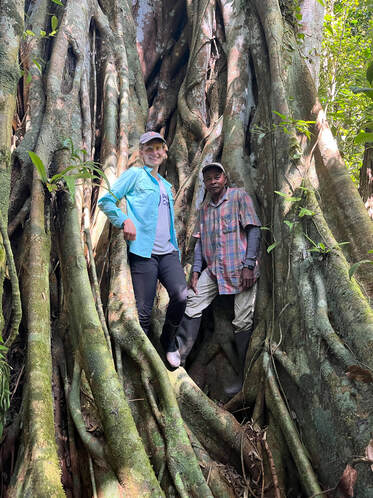

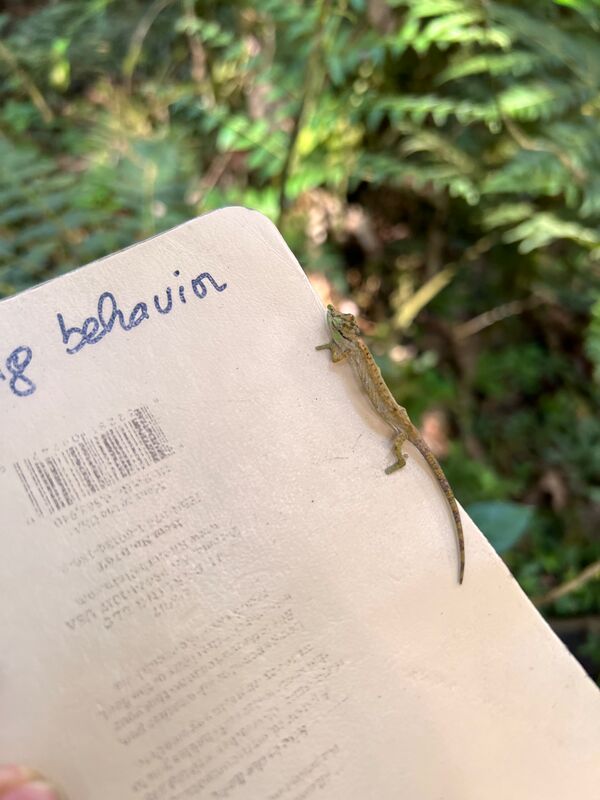

Text and photos by Kat Culbertson  Team Members Fetra and Edouard pose for a photo on the hike up to Marojejy Summit Team Members Fetra and Edouard pose for a photo on the hike up to Marojejy Summit Breath-taking rainforest covered mountains. Clear, cool streams overflowing with tadpoles. Adorable tiny – and I mean tiny – chameleons. Treacherous, steep, muddy, vine-covered terrain. Skipping over slippery rocks on your way to ‘work’. Hiding away in a tent for two weeks at a time. Fending off leaches, wasps, and scorpions… If this sounds like I’m describing a grand adventure, then fieldwork in eastern Madagascar may be right for you! While working in Madagascar across the past four years – both as a Peace Corps Volunteer and as an ecology researcher – I’ve had my fair share of both incredible highs and frustrating lows, but I’m excited to report that this last time around, I’ve had the best experience so far.  In the forest, sometimes the easiest path is a stream... In the forest, sometimes the easiest path is a stream... Starting in summer of 2023, I’ve been lucky enough to launch a project on rainforest regeneration at Marojejy National Park (with the aid of my advisors, my awesome collaborators at the Lemur Conservation Foundation, and three small fieldwork grants). This hyper-diverse reserve is a little patch of mountains – known as a massif – reaching across a 2,000 meter (6,000+ foot) gradient in the northeast corner of Madagascar. The park includes ecosystems ranging from lowland rainforest growing over 30 meters (100+ feet) tall to elevation-stunted dwarf topping out at 10 feet tall to alpine prairies. It is home to more than 2,000 plant species, 11 species of lemurs, and over 80 species of reptiles – just to name a fraction of its biodiversity. While scientific expeditions have been conducted in the park across 70 years, there is still little known about the vast majority of Marojejy’s species and the complex interactions between them. (In fact, one of the trees we snagged leaf samples from last year may be entirely new to science!)  A millipede crawls over the stump of a tree illegally harvested for the precious timber trade A millipede crawls over the stump of a tree illegally harvested for the precious timber trade Unfortunately, this international treasure is not immune to the numerous anthropogenic disturbances that threaten biodiversity globally these days. Forests continue to be cleared in across the region – including the more remote reaches of Marojejy park itself – for expansion of cultivation, fuelwood, and timber products. Illegal extraction of precious woods – especially rosewood and ebony – for thirsty international markets also continues deep within the park, a vast reserve of over 50,000ha (193 square miles) in which it’s easy to hide and challenging to patrol… due to a combination of challenging terrain, poor infrastructure, and lack of funding. Of course, climate change is also affecting the resiliency of the park’s forests and interactions between species across the region – in ways that we don’t know, especially given the lack of baseline data.  Kat (the author) and local botanical expert Mr. Edouard pose for a photo next to a giant strangler fig Kat (the author) and local botanical expert Mr. Edouard pose for a photo next to a giant strangler fig A conservation situation as complex as this one necessitates a multi-pronged approach to ensure that ecosystems and the biodiversity they contain are preserved for future generations. One key aspect of ecosystem conservation, especially in the face of ongoing deforestation and legitimate demand for timber products, is forest restoration. While tree-planting is currently a hot topic – for its role in carbon sequestration, alongside biodiversity conservation – little is actually known about how to ensure that a scattered saplings develop into a functioning forest ecosystem. This process of natural forest regeneration hinges on a variety of factors that are influenced by specific ecosystems and context, including how degraded the site’s soil is, how far seed-producing trees are from the deforested site, and whether any seed-dispersing critters (such as lemurs and birds) are still around. The further away a restoration site is from the forest, the longer it’s been used by humans, and the more anthropogenic factors nearby that could create new disturbances, the more complicated forest regeneration becomes, and the more divergent trajectories it could take. Unfortunately, few of these trajectories may result in a forest resembling the original one! The goal of restoration, or assisted natural regeneration, is to ensure forests are back on track to re-growing through eliminating some of the key barriers that are currently blocking the natural regeneration pathway. The relative importance of these barriers varies in different places and different ecosystems, and currently little is known about which ones are the most important to address in Madagascar. Extensive regenerating areas in Marojejy, previously cleared and cultivated, but sitting within a matrix of primary rainforest and abandoned for 25+ years, present a unique opportunity to understand natural forest regeneration pathways and understand the most important barriers to restoration in this context. This past year’s fieldwork – the actual ‘work’ component of it – involved surveying various regenerating forest areas to assess the type and number of trees growing in them, and evidence for regeneration processes. While I’m still working through the data, the preliminary takeaway is unfortunately that even forests in more-ideal regeneration conditions need our help: Even after 60+ years post-abandonment, old fields in the park are simply thickets of tall herbaceous vegetation, with no or very few trees present. This is a phenomenon known as ‘arrested regeneration’, when an ecosystem gets ‘stuck’ at an early stage along its regeneration journey, and may remain there for decades without additional disturbances or interventions.

We’re not sure why this is happening at Marojejy, though it likely is governed by the balance of dispersal factors (are there enough animals around to disperse seeds into regenerating areas?) and competition factors (do herbaceous plants and/or vines grow faster than, and thus outcompete or strangle young trees?), as well as the underlying dynamics of climate change (is the climate simply less suited for forest recovery now than it was 50 years ago?). I’m currently en route back to the field, where I’ll be working with my team to set up an disentangling some of these factors. We hope that this project will inform future restoration and ecosystem management actions in this region and beyond. Stay tuned for the next stages of this research journey! Text by Fetratiana Rakotomanga

We began our wonderful way in Antananarivo (Tana), where I met my mentor and several other members of the Razafindratsima lab. These connections and planning meetings set a strong foundation to strengthen our knowledge, skills and experiences. Our fieldwork had two different parts, the first month was held at KAFS or Kianjavato Ahmason Field Station, Vatovavy region. The place was calm and peaceful. The friendly team we worked with made it more pleasant too. We had the chance to participate in one of their plantation events in a large gap surrounded by forest. The astonishing view from famous mountains such as Sangasanga and Vatolahy shows how the complex and interesting landscape might influence the vegetation, especially the view from the top of Vatovavy, the region’s namesake. That view was memorable. The 11th of August, we left Kianjavato, heading to Marojejy. We were sad to leave the great team at Kianjavato but Marojejy National Park still held a special gift for us.

I enjoyed the contrast between two weeks inside the humid forest and two days in the city of Sambava. Staying in the forest felt like spending two weeks in paradise, as our guide Dezy always says, and then we came back to the civilization again for two days for supplies. Do not let me forget to say that the song of the stream and all the birds near every camp that we have been in gave us sweet dreams after hard work. I can say that I loved our fieldwork! Thanks also to our collaborators at Lemur Conservation Foundation (LCF) who gave us magnificent days near the ocean when we were out of the forest. Having a guide that is specialized in mammals and amphibians increased considerably our chance to see many endemic frogs like Mantella sp., Boophis sp.; reptile like Brookesia, almost all iconic birds and amphibians that Marojejy is known for, and also the “bokimbolo”: Hapalemur occidentalis that we can see very near at Camp 1. (Photo 6) Before leaving the first site, we made the hike of 5.1 km and over 4,000ft in elevation to the “sommet” the two last days. On our way, we saw the Helmet Vanga : Euryceros prevostii. We spent a night in camp 3, a very cold and quiet camp it was. We did not feel very lucky arriving at the top with rain, but it was and will always be a part of the adventure and still we had a wonderful experience. Sadly, during our fieldwork, we also witnessed many activities that threatened the ecosystem including forest clearance, wood harvesting and some lemur traps. These activities can have a huge impact on the biodiversity that the park shelters. Much work has been done before to try to prevent these illegal activities and conserve the forest, but there is still more to do, so we encourage you to stand with us for the sake of our nature. These ongoing threats to biodiversity show us up close how reforestation (the main research of my mentor) is important.

There is always a starting point for everyone but do not let that make you feel that you are not good enough. There will always be people who have already gone through your stage willing to help you, so I just want to say: “take the chance, give your best and enjoy”.

Text by Jessica Stubbs

Thus, when the lab offered me the opportunity to become a Field Technician in Madagascar, I felt as if I was finally able to realize my ecological decree and ameliorate the dissonance between my most profound academic passion and personal experience. Armed with robust rubber boots, a plethora of ambiguous antibiotics, and an inexplicable sense of loyalty to the ecosystems and lemurs I was yet to meet, I was ready for anything. The first week in Antananarivo was a vibrant and kinetic rush of unfamiliarity and culture. Scouring the teeming markets for field supplies, absorbing my first words of Malagasy, and ambling along the restless streets was exhilarating. Most exuberant, was having the momentous privilege to experience lab member Vero’s wedding. Dancing in effervescent swirls of Malagasy family members, consuming heaps of aromatic ravitoto, and reveling in the cultural exuberance of the wedding traditions was a singular experience of exceptional joy. The entangled vibrance of Antananarivo was a sensorial introduction to Madagascar and only a nascent glance into the incredible country I was soon to explore. While driving to Ranomafana, the boisterous contours of the city melted into expansive verdant hills, imbricating agricultural fields, and meandering brown streams. The landscape was punctuated by lines of laboring zebus, rich piles of fresh bricks, intimate huddles of market sellers, opinionated discourses among geese, and clusters of enthralled children.

After a few days gathering our supplies and coordinating our research objectives, we set off through banana fields and up arboraceous mountains to our campsite to begin the real work embedded within the forest.

Meals consisted of rice and beans, showers were taken in the river's embrace, purpose was found in the lemurs, and community thrived among the people and biota around us. The endless onslaught of news cycles, inundation of messages and emails, and perennial duty of academic and professional tasks faded into the immediacy and immensity of the forest. The profound reduction in external stimulus honed my abilities as a conservation practitioner and allowed my somatic and cerebral capabilities to unify in the research, questions, and wildlife that enveloped me.

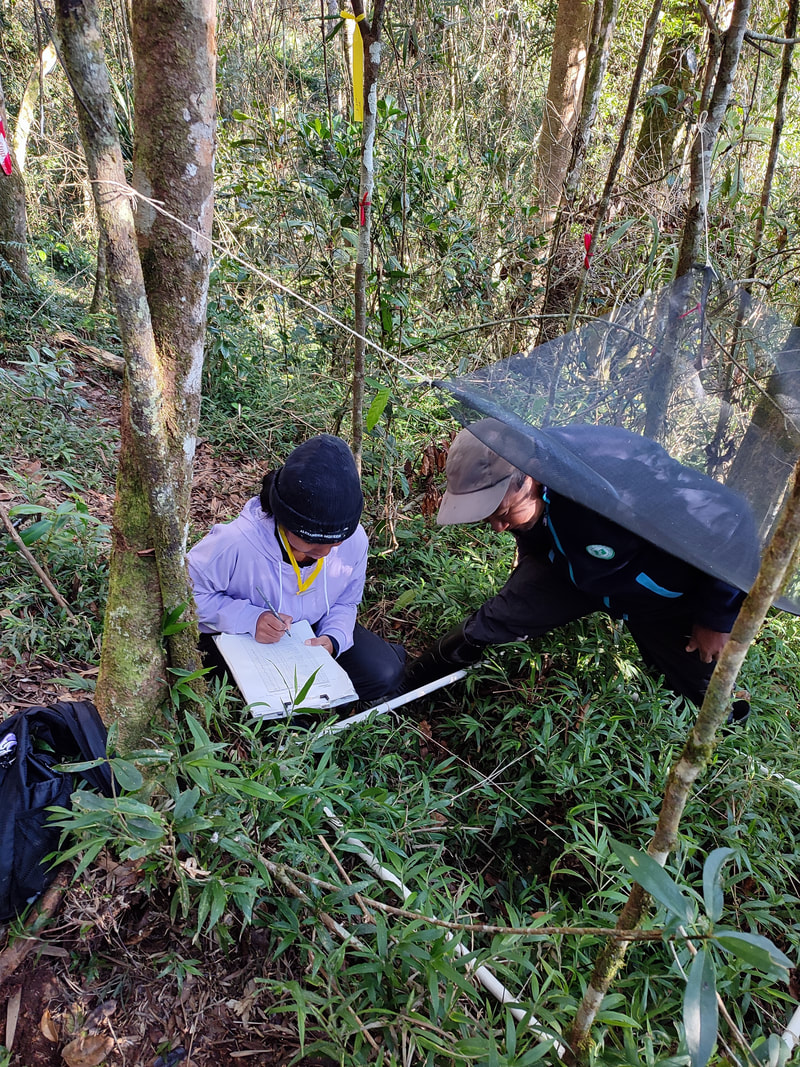

Everyday was met with a multitude of novel lessons, inspiring curiosities, interminable giggles, scientific inquiries, lemur connections, persistent leeches, and legions of rice and beans. Never before had I possessed so few material effects and external comforts, and yet felt so fulfilled. My mind was kinetic with research ideas, empirical conquests, and experimental propositions. After lemur follows, we would march to the lab (a makeshift arrangement of tarp and sticks) and dive into preparing fecal samples with multiple treatments to delineate how the lemur microbiome affects seed germination rates. Conducting innovative science in the middle of the forest truly instilled the importance of embracing constant agility, improvement, and adaptation in an environmental arena of finite resources and unlimited stochasticity. As an emerging conservation practitioner, these experiences fortified my scientific problem-solving dexterity and imprinted an enduring zeal for advancing research on the front lines of conservation. Beyond catalyzing the counters of my intellectual prowess, the endogenous connections and palpable kingship that developed with the lemurs and fellow field technicians were transformative. Camp members and field technicians became an instant troop of unwavering loyalty. Hundreds of hours spent in the forest welded us together interminably. Picking leeches off each other, sharing meals under the canopy, teaching plant varieties, exchanging languages, and collectively immersing in the centripetal intrigue of the lemurs infused every lemur follow with an immensity of supportive reciprocity. Back at camp, the enveloping sense of community transcended challenging conditions and crystallized into interrelational wisdoms, connections, and understandings. Playing dominos with fierce determination, boldly pioneering novel food concoctions, piling around the fire, and passing jugs of steaming burnt rice water around the table were liminal moments of enduring warmth. Punctuating our time at camp were both restful and exuberant sojourns at the ValBIo Research Station. There, we extracted DNA by processing our fecal samples utilizing advanced laboratory techniques. In the lab, I sharped my pipetting precision, gained confidence mixing fragile chemicals, and advanced my ability to curate immaculate lab playlists to foster the ideal musical feng shui for science. Spending afternoons in the lab, meals with impassioned researchers, and evenings organizing supplies and trading lemur stories with volunteers further reinforced my avidity and esteem for the imperative research we were conducting. From skillfully collecting lemur fecal deposits from the forest floor to methodically purifying and extracting genetic information from samples in the lab, I was developing a comprehensive understanding of advancing conservation research.

My Forest Adventure: Ten Weeks of Discovery and Learning Text by Diary Randriamora, a Malagasy student who spent last summer working with our research group in Ranomafana through the National Geographic Society's STEM Field Assistant Mentorship program

Working in a rainforest that rains a lot is itself also very challenging. One day, we had a heavy rainstorm on our way to our campsite in Valohoaka. The rain was so strong that it soaked my rain boots and made my feet swell. I also had many leeches stuck to my feet, which was very unpleasant. But I did not let that ruin my mood, because I knew that rain was essential for this tropical forest ecosystem. I embraced the adventure and enjoyed every moment!

I have a message for those who love research like me: don’t be afraid to try something you like and see as beneficial for you because there is always a good way behind adventure. Be determined to achieve your goals and don’t let them be just dreams!

Torrential rain, ravenous leeches, rainforest bramble, and the all-pervasive bean! Raine Zulueta, an undergraduate student at the University of California Berkeley, shares his field experience working with the field team in Ranomafana, Madagascar.

Time would pass in the car, and it felt as though I had gained a heightened sense of patience as I took notice of the passage of time. After around 15 hours, complete with dark winding roads up the mountainside, we would eventually arrive. Our legs numb and figuratively full of static, we turned in for two nights to relax before our very first day in the field. This was only the beginning of this two-month journey, and I was more than excited to take my first steps into the rainforest.

Time would pass, and by mid-July I had reached a rhythm and routine that felt like second nature. I would scurry down to the dining table, consisting of local wooden planks fastened with homely leather straps and cordage, beginning to devour my breakfast typically composed of either meat or eggs, rice, and beans At around 7:00 in the morning, we would begin to hike to the research site up the mountain, to begin our search for one of the three lemur species within the project: Eulemur rufifrons, Eulemur rubriventer, and Varecia variegata editorum. My responsibility within the project revolved around tracking and taking note of their behavior every five minutes. With my Rite-in-the-Rain handy, I would utilize different codes that would act as shorthand to describe what the lemurs were doing. For example, sleeping was shortened to “SL”, feeding to “F”, and even defecating and drinking water to “D” and “DW” respectively. To help gain experience in the different species, I would be placed onto one of the three different teams every week or so. This entailed mass amounts of learning through the experience itself, which I particularly enjoyed. It was fascinating to take note of the different temperaments and personalities that each species sustained, in addition to the behavioral patterns that would naturally arise. One of my fondest memories in the field happened during an Eulemur rubriventer follow. As you can likely assume, it rains quite a lot in the rainforest, and truthfully I expected the same if not more before arriving to Ranomafana National Park. But on this particular day, I had seen rain in a way I had never seen it before. It was truly torrential, hefty droplets of water plummeting at speeds and in sheer volumes unbeknownst to me as a Californian. We were bounding up the mountain, slashing through the rainforest foliage while chasing a red-bellied lemur as it sprung from canopy to canopy. Seemingly increasing in speed, the male lemur swiftly scaled the mountainside, the slashing of brush audibly constant, almost rhythmic. Crossing through ephemeral rivers, waterfalls, slippery rocks and more, we eventually reached the mountain’s peak. Upon our arrival we were greeted by a sight I hold dearly to my heart, what I think made this lemur follow so special: a lone E. rubriventer female sitting in the middle of a clearing, looking up at the canopy and rainfall misting her visage, almost in admiration. While the rain completely soaked all of our belongings, my backpack and rain coat dripping to the touch, I found solace in the cooling relief that it delivered as I found my body fatigued from the scramble up the mountain. This is but one of many memories created, stories encountered, and experiences lived, throughout this field season.

My association with field work, yet alone tropical fieldwork, could be expressed as a blank slate. Lemur research in the tropical rainforests of Madagascar is not where I saw myself five years ago, but I am genuinely more than grateful to have ended up where I did. As niche as this entire summer was, I firmly believe that this trip helped me find myself on levels deeper than I could ever imagine, all while learning what it means to conduct research and contribute to crucial conservation efforts.

|

We're using this space to share updates on our adventures in the field. Archives

May 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed