|

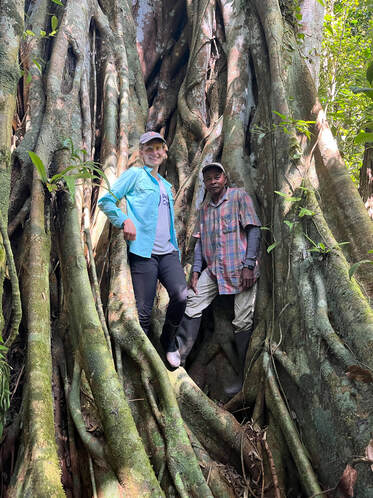

Text and photos by Kat Culbertson  Team Members Fetra and Edouard pose for a photo on the hike up to Marojejy Summit Team Members Fetra and Edouard pose for a photo on the hike up to Marojejy Summit Breath-taking rainforest covered mountains. Clear, cool streams overflowing with tadpoles. Adorable tiny – and I mean tiny – chameleons. Treacherous, steep, muddy, vine-covered terrain. Skipping over slippery rocks on your way to ‘work’. Hiding away in a tent for two weeks at a time. Fending off leaches, wasps, and scorpions… If this sounds like I’m describing a grand adventure, then fieldwork in eastern Madagascar may be right for you! While working in Madagascar across the past four years – both as a Peace Corps Volunteer and as an ecology researcher – I’ve had my fair share of both incredible highs and frustrating lows, but I’m excited to report that this last time around, I’ve had the best experience so far.  In the forest, sometimes the easiest path is a stream... In the forest, sometimes the easiest path is a stream... Starting in summer of 2023, I’ve been lucky enough to launch a project on rainforest regeneration at Marojejy National Park (with the aid of my advisors, my awesome collaborators at the Lemur Conservation Foundation, and three small fieldwork grants). This hyper-diverse reserve is a little patch of mountains – known as a massif – reaching across a 2,000 meter (6,000+ foot) gradient in the northeast corner of Madagascar. The park includes ecosystems ranging from lowland rainforest growing over 30 meters (100+ feet) tall to elevation-stunted dwarf topping out at 10 feet tall to alpine prairies. It is home to more than 2,000 plant species, 11 species of lemurs, and over 80 species of reptiles – just to name a fraction of its biodiversity. While scientific expeditions have been conducted in the park across 70 years, there is still little known about the vast majority of Marojejy’s species and the complex interactions between them. (In fact, one of the trees we snagged leaf samples from last year may be entirely new to science!)  A millipede crawls over the stump of a tree illegally harvested for the precious timber trade A millipede crawls over the stump of a tree illegally harvested for the precious timber trade Unfortunately, this international treasure is not immune to the numerous anthropogenic disturbances that threaten biodiversity globally these days. Forests continue to be cleared in across the region – including the more remote reaches of Marojejy park itself – for expansion of cultivation, fuelwood, and timber products. Illegal extraction of precious woods – especially rosewood and ebony – for thirsty international markets also continues deep within the park, a vast reserve of over 50,000ha (193 square miles) in which it’s easy to hide and challenging to patrol… due to a combination of challenging terrain, poor infrastructure, and lack of funding. Of course, climate change is also affecting the resiliency of the park’s forests and interactions between species across the region – in ways that we don’t know, especially given the lack of baseline data.  Kat (the author) and local botanical expert Mr. Edouard pose for a photo next to a giant strangler fig Kat (the author) and local botanical expert Mr. Edouard pose for a photo next to a giant strangler fig A conservation situation as complex as this one necessitates a multi-pronged approach to ensure that ecosystems and the biodiversity they contain are preserved for future generations. One key aspect of ecosystem conservation, especially in the face of ongoing deforestation and legitimate demand for timber products, is forest restoration. While tree-planting is currently a hot topic – for its role in carbon sequestration, alongside biodiversity conservation – little is actually known about how to ensure that a scattered saplings develop into a functioning forest ecosystem. This process of natural forest regeneration hinges on a variety of factors that are influenced by specific ecosystems and context, including how degraded the site’s soil is, how far seed-producing trees are from the deforested site, and whether any seed-dispersing critters (such as lemurs and birds) are still around. The further away a restoration site is from the forest, the longer it’s been used by humans, and the more anthropogenic factors nearby that could create new disturbances, the more complicated forest regeneration becomes, and the more divergent trajectories it could take. Unfortunately, few of these trajectories may result in a forest resembling the original one! The goal of restoration, or assisted natural regeneration, is to ensure forests are back on track to re-growing through eliminating some of the key barriers that are currently blocking the natural regeneration pathway. The relative importance of these barriers varies in different places and different ecosystems, and currently little is known about which ones are the most important to address in Madagascar. Extensive regenerating areas in Marojejy, previously cleared and cultivated, but sitting within a matrix of primary rainforest and abandoned for 25+ years, present a unique opportunity to understand natural forest regeneration pathways and understand the most important barriers to restoration in this context. This past year’s fieldwork – the actual ‘work’ component of it – involved surveying various regenerating forest areas to assess the type and number of trees growing in them, and evidence for regeneration processes. While I’m still working through the data, the preliminary takeaway is unfortunately that even forests in more-ideal regeneration conditions need our help: Even after 60+ years post-abandonment, old fields in the park are simply thickets of tall herbaceous vegetation, with no or very few trees present. This is a phenomenon known as ‘arrested regeneration’, when an ecosystem gets ‘stuck’ at an early stage along its regeneration journey, and may remain there for decades without additional disturbances or interventions.

We’re not sure why this is happening at Marojejy, though it likely is governed by the balance of dispersal factors (are there enough animals around to disperse seeds into regenerating areas?) and competition factors (do herbaceous plants and/or vines grow faster than, and thus outcompete or strangle young trees?), as well as the underlying dynamics of climate change (is the climate simply less suited for forest recovery now than it was 50 years ago?). I’m currently en route back to the field, where I’ll be working with my team to set up an disentangling some of these factors. We hope that this project will inform future restoration and ecosystem management actions in this region and beyond. Stay tuned for the next stages of this research journey! Comments are closed.

|

We're using this space to share updates on our adventures in the field. Archives

May 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed